After nearly three weeks of extensive testing and data analysis, NASA executives said Friday they have confidence in Boeing frequently delayed Starliner crew capsule can launch safely “as is” on June 1, saying a small helium leak in the ship’s propulsion system does not pose a flight safety concern.

Steve Stich, manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, said that even if a suspect shirt-sized rubber seal in the lines leading to a specific thruster were to fail completely in flight — resulting in a leak rate 100 times worse than what has been observed so far – the Starliner was still able to fly safely.

“If we get it wrong somewhere, we can handle four more leaks,” he said. “And we could address this particular leak if the leak rate were to increase, even up to 100 times in this (propulsion module).”

What will now be a launch delay of almost a month was necessary because “we had to take the time to work through this analysis, and to understand the helium leak and its implications,” Stich said.

It also gives staff time off over the Memorial Day holiday weekend.

The Starliner’s two NASA crew members, Commander Barry “Butch” Wilmore and co-pilot Sunita Williams, plan to fly back to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida next Tuesday to prepare for launch from the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station atop an Atlas 5 rocket at 12:25 p.m. EDT June 1.

If all goes well, they will dock with the International Space Station the next day and return to Earth on June 10.

Wilmore and Williams were preparing for launch on May 6 when the countdown was aborted due to problems with an oxygen pressure relief valve in the Centaur upper stage of their Atlas 5. Rocket builder United Launch Alliance towed the booster back to a processing facility and replaced the valve without incident.

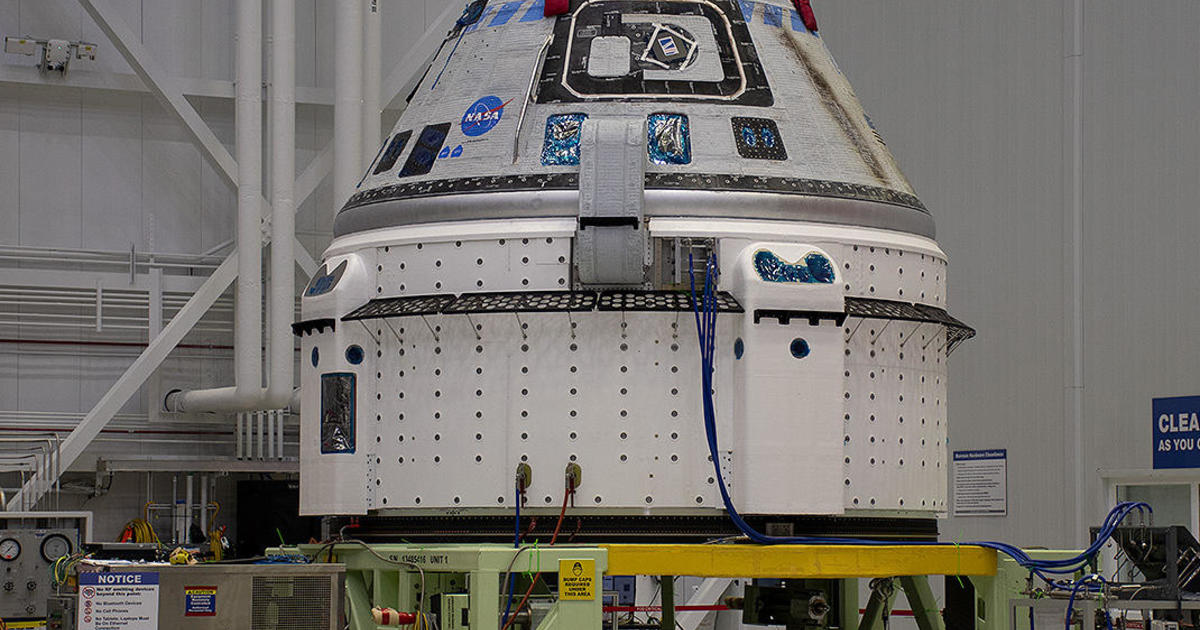

At the same time, Boeing engineers began a detailed investigation from a small helium leak in one of the Starliner’s four propulsion modules, known as ‘doghouses’, which emerged when the valves were closed as part of normal post-scrub procedures.

The leak was eventually traced to a flange where propellant lines feeding a specific thrust from the reaction control system in the port doghouse meet. The Starliner is equipped with 28 RCS jets and helium is used to pressurize the propellant lines, opening and closing the valves in each doghouse as necessary.

Because traces of highly toxic propellants could still be present in the lines, the seal could not be replaced or even inspected while the capsule was still attached to the Atlas 5. The Starliner would first have to be towed back to the Boeing processing hangar on Kennedylaan. Space Center for invasive repairs that would cause a longer delay.

Instead, NASA and Boeing ordered testing and analysis to fully understand the leak and what problems it could cause during flight. The observed leak rate did not appear to be a problem, but engineers had to gain confidence that it would not worsen dramatically. They also wanted to make sure no other systems were affected.

Stich said the seal in question had likely shrunk or had a minor defect, allowing helium to slip through. But tests showed that even if the seal was removed from the flange, the Starliner could still fly safely. The helium manifold in question could be isolated and the Starliner’s many other thrusters could easily compensate for this.

Mark Nappi, Starliner program manager at Boeing, said the May 6 launch scrub had a “silver lining” because it brought the helium leak to everyone’s attention and “we now know exactly where it was, we’ve done all the work to determine the cause to understand. and that will help us improve the system in the future.”

“If we had launched … it would have been a safe flight and a successful flight,” he said, “but we wouldn’t have known as much as we know now.”

That includes one unexpected result, what Stich called “a design vulnerability.” The research shows that in the very remote chance of major problems with two adjacent doghouses, including the one with the helium leak, the Starliner could lose redundancy to fire the thrusters needed to fall out of orbit to re-enter .

The Starliner is designed to support three redundant de-orbit capabilities. In one of them, braking is performed with four powerful Orbital Maneuvering and Attitude Control (OMAC) thrusters. The burn can also be accomplished with just two operating OMAC jets, or with eight smaller RCS thrusters, by firing them longer than planned.

Under the right conditions, if adjacent doghouse modules are inoperative, the Starliner could lose full RCS deorbit capability with eight thrusters.

“We worked with the thruster vendor, Boeing and our NASA team to come up with a redundant method to perform the orbit burn, dividing it into two burns of about 10 minutes each, spaced apart of 80 minutes. a deorbit burn with four RCS thrusters and to regain the capabilities of the original system,” Stich said.