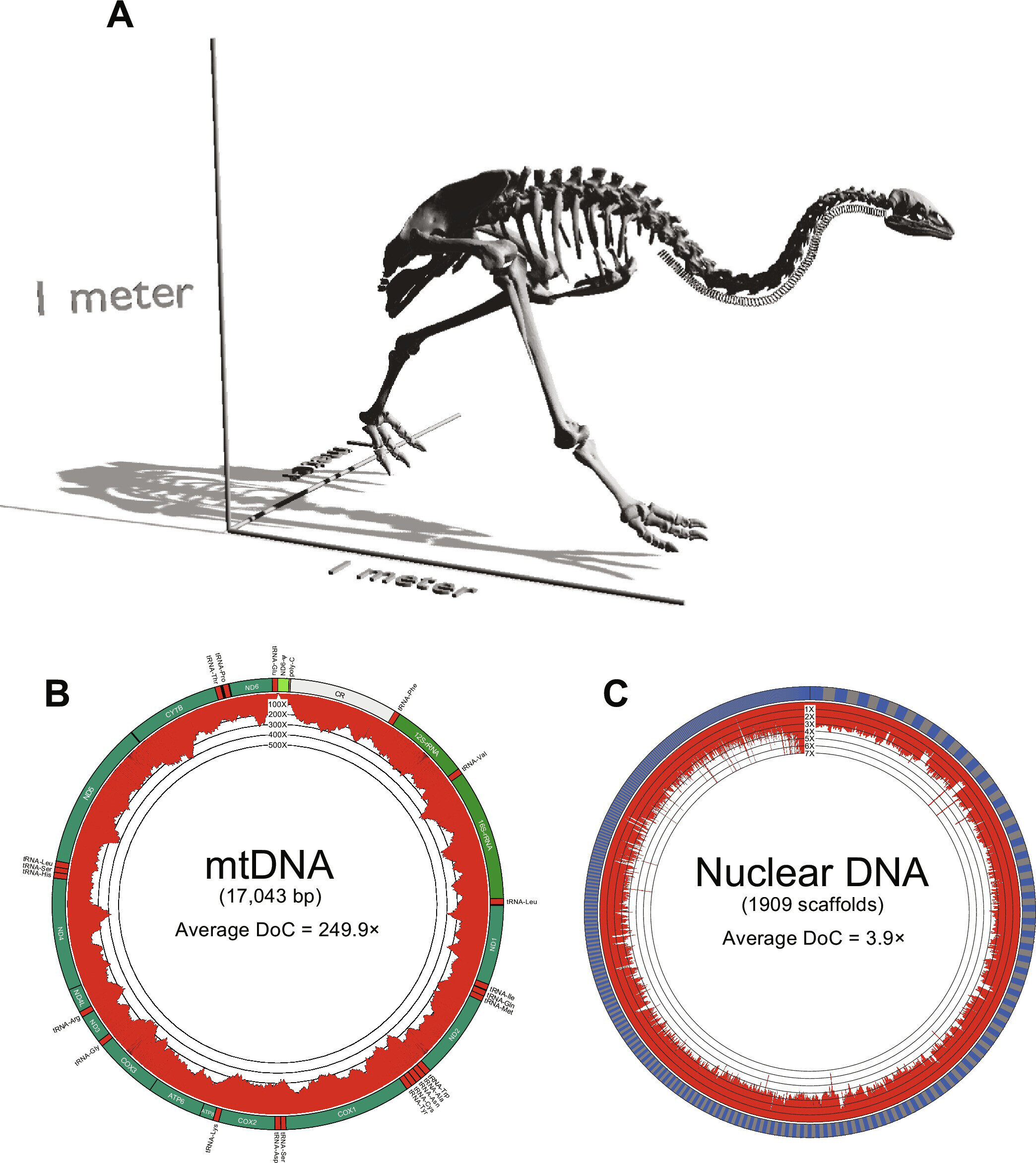

Design nuclear and mitochondrial genome assemblies of the small bush moa. (A) 3D image of a small bush moa skeleton. (B) De novo assembled mitochondrial genome, with locations of annotated genes and RNAs indicated. The inward-facing graph shows the Depth of Coverage (DoC) per base. (C) Reference-based nuclear genome assembly (illustrated for the original moa assembly). Credit: Scientific progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adj6823

× close to

Design nuclear and mitochondrial genome assemblies of the small bush moa. (A) 3D image of a small bush moa skeleton. (B) De novo assembled mitochondrial genome, with locations of annotated genes and RNAs indicated. The inward-facing graph shows the Depth of Coverage (DoC) per base. (C) Reference-based nuclear genome assembly (illustrated for the original moa assembly). Credit: Scientific progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adj6823

A team of evolutionary biologists at Harvard University, working with colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence, East Carolina University, Osaka University and the University of Toronto, have reconstructed the genome of an extinct species of flightless bird that has become famous. like the small bush moa.

In their research, published in the journal Scientific progressthe group’s sequenced DNA recovered from a fossilized bone found on South Island (the largest and southernmost of the two main islands that make up New Zealand).

The little forest moa was once one of the largest birds in the world. It was about the size of a modern turkey and became extinct shortly after the arrival of human settlers in New Zealand. Before that, they roamed the forested islands of New Zealand for millions of years. They were unique in their complete lack of wings. Previous partial sequencing showed that they had the genes needed to grow wings, but over time they had mutated as the birds slowly became flightless land dwellers.

The fossil used by the research team came from a bird that was one of nine species of extinct Anomalopteryx didiformis. The team describes their results as recovering a complete mitochondrial genome from a male moa nuclear genome – a feat that was considered a challenge.

After sequencing, the researchers discovered that the birds had been able to see in the ultraviolet spectrum – an ability that would have helped them catch hidden prey. They also had what the group describes as a sensitivity to bitter foods – a trait common in modern birds. The data also showed that the birds’ likely population had once been as high as 240,000 and that the birds diverged from their closest relatives about 70 million years ago.

The research team suggests that their results, in addition to providing new information about the little bush moa, should also serve as a new resource for other teams working to better understand bird evolution.

More information:

Scott V. Edwards et al., A nuclear genome assembly of an extinct flightless bird, the little bush moa, Scientific progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adj6823

Magazine information:

Scientific progress

© 2024 Science X Network