Circular depressions about 500 feet wide off the coast of Central California are quite old and owe their longevity to sediment flows, new research shows. However, the original cause has yet to be discovered.

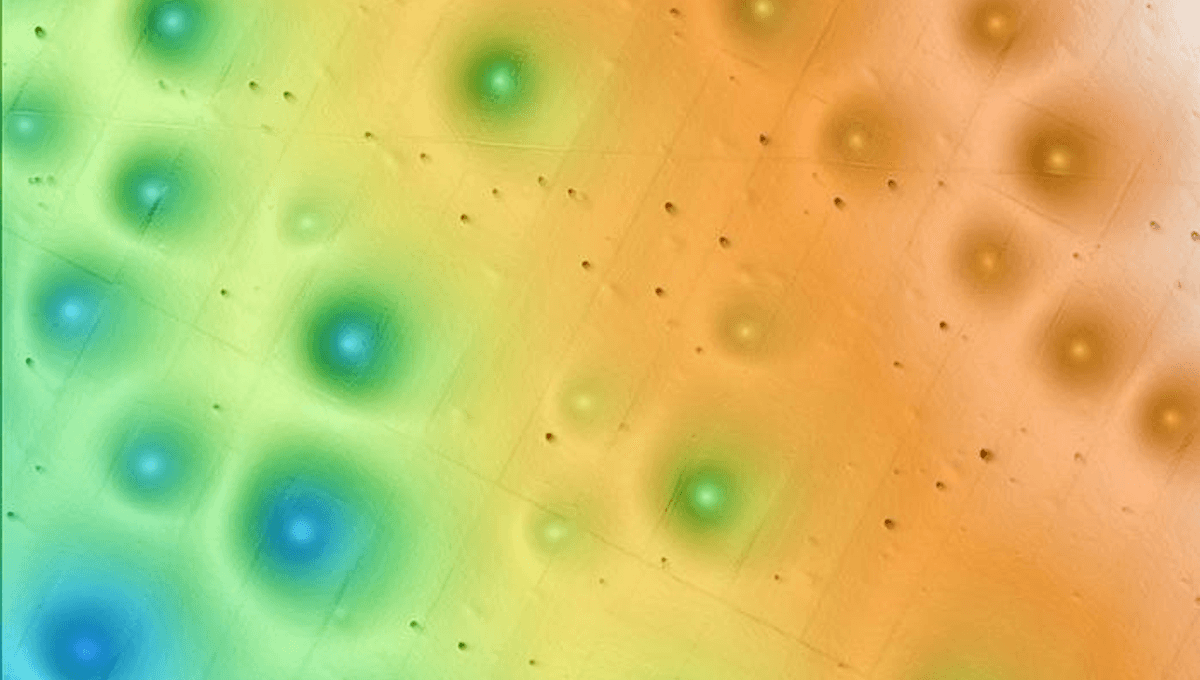

The Sur Pockmark Field has puzzled oceanographers since its discovery in 1998. More than 5,000 shallow circular depressions are packed into an area the size of Los Angeles, about 40 kilometers (26 miles) off the coast of Big Sur, Central California.

The formations average only about 5 meters deep, although some can be almost ten times that deep. Similar formations elsewhere in the world are attributed to pockets of methane escaping through sediments, such as the craters that recently appeared in Siberia.

The release of all that methane is a serious problem for the planet, given the greenhouse effect of the gas when it reaches the surface, but there is also a more local problem. The area near Big Sur is marked for offshore wind farms, and it would be a problem if methane were to bubble up where the floating towers are anchored.

This spurred the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) to investigate the subject more deeply, and they found another explanation. The researchers concluded that the depressions are caused by gravity flows of sediment, a kind of underwater avalanche of mud and sand.

“There are many unanswered questions about the seafloor and its processes,” Eve Lundsten of MBARI said in a statement. “This research provides important seafloor data for resource managers and others considering potential offshore locations for underwater infrastructure to guide their decision-making.”

Lundsten and co-authors began by deploying underwater robots to map more than 300 pockmarks and their surroundings, with a resolution that surface-based sonar could not match. They also took more than 500 sediment samples in and around five wells, which showed no sign of methane.

A clue to the cause lies in something not apparent on maps; the field lies on the sloping continental margin, between the shelf and the deep ocean. That slope creates conditions for massive gravity currents, and the team found that the sediment includes layers of sandy deposits called turbidites, left behind by gravity currents over the past 280,000 years. The most recent flow occurred about 14,000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age.

The team’s conclusion is that the gravity currents erode sediments that accumulate in the pockmarks under more normal conditions, preserving the notches, but the initial formation process remains a mystery.

“We collected a huge amount of data, which allowed us to make a surprising connection between pockmarks and the gravity flows of sediment. We couldn’t determine exactly how these pockmarks initially formed, but with MBARI’s advanced underwater technology, we have gained new insight into how and why these features have persisted on the seafloor for hundreds of thousands of years,” Lundsten said.

Adding to the mystery of pockmark formation is that they are fairly evenly distributed, a common feature of pockmarked fields elsewhere. They range from 10 to 700 meters (33 to 2,297 feet), with the larger ones being in deeper waters. The team also found evidence that individual pockmarks can sometimes migrate along the ocean floor.

Wind farm developers may not like the sound of massive avalanche-like activity in their field, but the timescales between these events suggest they are less threatening than methane emissions.

The work makes the Sur Pockmark Field one of the best-studied offshore areas in North America, and therefore probably in the world.

The research has been published open access in the Journal of Geophysical Research Earth Surface.