Planet Earth has been around for 4.5 billion years, anyway, and a lot has changed in that time. What started as a ball of molten, swirling magma eventually cooled and developed a few small tectonic plates; About a few billion years later, the planet was covered in various supercontinent formations and teeming with life.

But the Earth is still young, cosmologically speaking. We’re barely a third of the way through its likely lifespan, and there’s still plenty of changes to come.

Unfortunately, it looks like we probably won’t survive them. According to a study published last year, which used supercomputers to model the climate over the next 250 million years, the world of the future will again be dominated by a single supercontinent – and will be virtually impossible for any mammal be uninhabitable.

“The prospects in the distant future appear very bleak,” confirmed Alexander Farnsworth, Senior Research Associate at the University of Bristol’s Cabot Institute for the Environment and lead author of the study, in a statement.

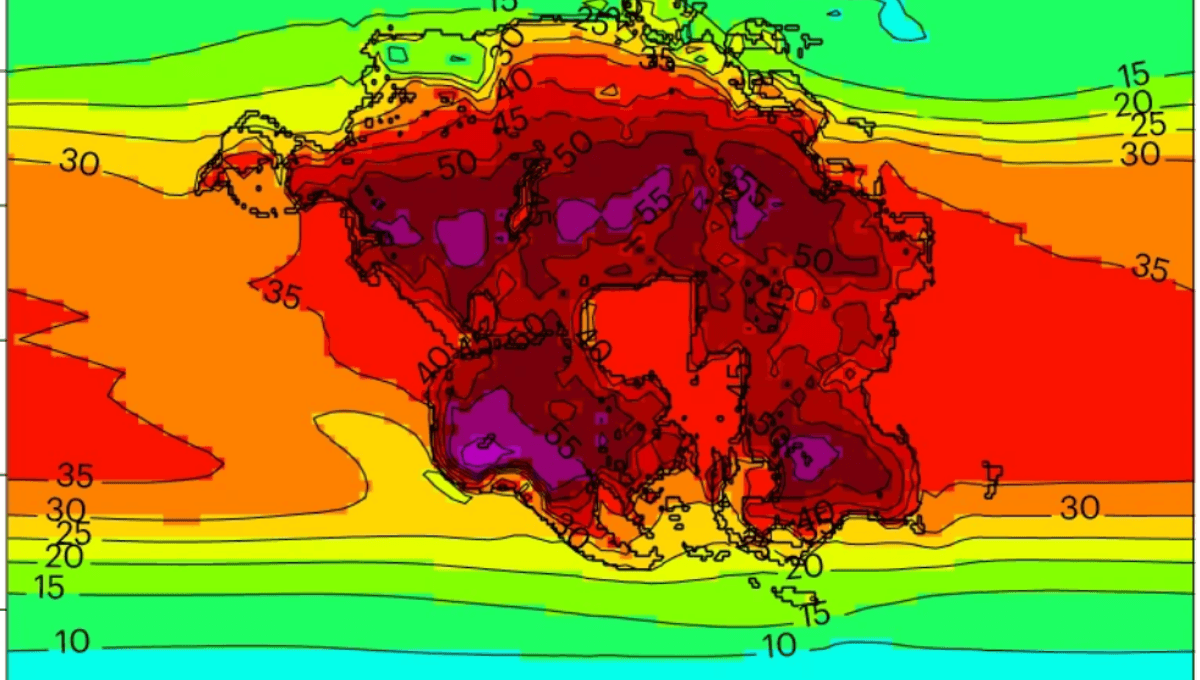

“Carbon dioxide levels could be double current levels,” he explained. “Given that the Sun is also expected to emit about 2.5 percent more radiation and the supercontinent is mainly in the hot, humid tropics, much of the planet could experience temperatures between 40 and 70°C. [104 to 158 °F].”

The new supercontinent – known as Pangea Ultima, referring to the old supercontinent Pangea – would create a “triple whammy,” Farnsworth said: Not only would the world have to deal with about 50 percent more CO2 in the atmosphere than current levels; not only would the Sun be hotter than it is today – this happens to all stars as they age, due to the evolving push-and-pull between gravity and fusion taking place in the core – but the very size of the supercontinent itself would ensure that it is almost entirely uninhabitable. That’s due to the continentality effect—the fact that coastal areas are cooler and wetter than inland areas, and the reason why summer and winter temperatures in, say, Lawrence, Kansas, are so much more extreme than in Baltimore.

“The result is a largely hostile environment with no food and water sources for mammals,” Farnsworth said. “Widespread temperatures between 40 and 50 degrees Celsius, and even greater daily extremes, exacerbated by high humidity, would ultimately seal our fate. Humans – like many other species – would die because they are unable to dissipate this heat through sweat, which cools their bodies.”

And here’s the kicker: that’s kind of a best-case scenario. “We think CO2 could rise from around 400 parts per million (ppm) today to more than 600 ppm many millions of years in the future,” explains Benjamin Mills, Professor of Earth System Evolution at the University of Leeds, who led the calculations for the study. “Of course, this assumes that people will stop burning fossil fuels, otherwise we will see these numbers much, much sooner.”

So while the study paints an ominous picture of Earth many millions of years from now, the authors warn us not to forget the problems that lie around the corner. “It is crucial not to lose sight of our current climate crisis, which is the result of human emissions of greenhouse gases,” warned Eunice Lo, a Research Fellow in Climate Change and Health at the University of Bristol and co- author of the paper.

“We are already experiencing extreme heat that is harmful to human health,” she emphasizes. “That’s why it’s critical to reach net-zero emissions as quickly as possible.”

The study has been published in the journal Nature Geoscience.