Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, editor of the FT, selects her favorite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Rishi Sunak declared inflation back to “normal” at 7am on Wednesday, ending the pain of rising prices. Less than twelve hours later, the Prime Minister took this opportunity to launch a surprise general election.

Most elections are decided on the economy. Sunak, charting the economic horizon, concluded that this “key moment” was about as good as it could get in the near future.

Sunak and Chancellor Jeremy Hunt concluded they should go to the country in July, according to senior party officials, thanks to the improving economy and with inflation of just 2.3 percent in April.

Grant Fitzner, chief economist at the Office for National Statistics, said this month that the economy was going “gangbusters” after growing 0.6 percent in the first quarter. Real wages have risen for ten months in a row.

According to people aware of Sunak and Hunt’s ideas, the outlook for the coming months was seen as less favorable, tipping the scales towards a summer rather than autumn election.

Markets expect inflation to rise in the coming months, while expectations of an early rate cut by the Bank of England will decline. More importantly, Hunt had given up hope of tax cuts before the election.

The Chancellor informed his colleagues that there would be no autumn statement as government finances would not be strong enough to allow him to deliver on his hoped-for further 2p cuts to national insurance.

Waiting until the autumn left open the prospect of more party infighting, leadership speculation and defections by disgruntled Tory MPs, while the economic benefit was limited.

But so far there is little evidence that the recent good news on the economy is translating into a political boost for Sunak or the Conservatives. Tory MPs often complain that “the voters aren’t listening”.

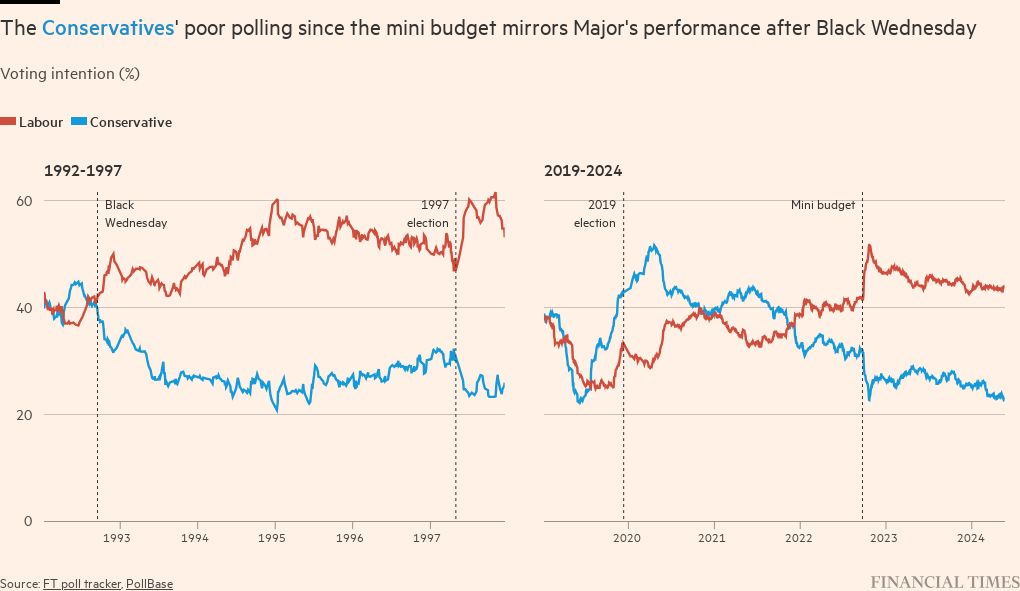

Opinion polls show the Tories suffered a decisive blow to their reputation for economic competence – usually a defining factor in a general election – during Liz Truss’s disastrous 49-day premiership in 2022.

Sunak has failed to regain much ground since then, even as he claimed the fall in headline inflation in April was evidence that “the tough decisions we have made are paying off”.

YouGov polling on who voters “trust in the economy” shows Tory support fell during Boris Johnson’s time as prime minister, before falling further after the Truss government’s “mini” budget in September 2022.

The furore saw Labor overtake the Conservatives on the economy, a lead the country has maintained during Sunak’s time as prime minister despite steadily rising inflation.

“Stability is change” has become Labour’s official economic mantra; party leader Sir Keir Starmer, the political debate regularly returns to the chaotic days of the Truss premiership.

A key part of the problem, as Hunt acknowledged Wednesday, is that better economic data is not significantly feeding into household budgets. “It’s hard,” he said, admitting that some voters felt “bruised and battered” by economic shocks.

Hunt and Sunak’s argument is that voters will soon feel better off and should “stick to the plan”, and that switching to Labor would be a dangerous leap in the dark.

“Brighter days lie ahead, but only if we stick to the plan to improve economic security and opportunity for all,” Sunak said earlier on Wednesday.

The problem for Sunak is that time is running out. Since the economy only emerged from a mild recession in early 2024, the public seems in no mood to give credit to the Prime Minister.

Anthony Wells, senior political pollster at YouGov, said that while Tory polls on the economy were up slightly, they were only “slightly less terrible” than before.

Wells drew parallels with the devastating economic shock of Black Wednesday in 1992, when Britain was forced to leave the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, dealing a major blow to the economic reputation of John Major’s government.

He added that by the time of the 1997 election the Conservatives had recovered some of that damage and were “roughly neck and neck” with Tony Blair’s Labor Party on the economy.

But even the return to parity had taken almost five years – not the 18 months since the Truss debacle – and Major’s government went into the 1997 election with 4 percent growth and low inflation, not the bloodless growth that we have recently seen in Britain.

Lord Norman Lamont, Tory chancellor at the time of Black Wednesday, said that while the Truss Budget had not caused much lasting economic damage, it had caused reputational damage.

Lamont said many of Britain’s economic problems were hardly the fault of Sunak’s government, but that “people are sometimes very unreasonable in their expectations”.

Rachel Reeves, shadow chancellor, argued that the Tories would not take any credit for falling inflation.

“I can understand why a Conservative Prime Minister richer than the King would want to run to the television studios to tell the British they have never had it better,” Reeves wrote in the Sun newspaper.

But she said voters only had to look at their bank balance and the price of the weekly shop to know they were worse off.