Credit: Flinders University

× close to

Credit: Flinders University

The patterns of early humans’ dispersal across continents and islands are hotly debated, but according to a new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of SciencesPleistocene hunter-gatherers settled in Cyprus thousands of years earlier than previously thought.

Investigating the timing of the first human occupation of Cyprus, research led by Professor Corey Bradshaw of Flinders University found that large islands in the Mediterranean were attractive and favorable destinations for Palaeolithic peoples.

These findings refute previous studies that suggested that Mediterranean islands would have been inaccessible and inhospitable to Pleistocene hunter-gatherer societies.

Professor Bradshaw, together with Dr Theodora Moutsiou, Dr Christian Reepmeyer and others, used archaeological data, climate estimates and demographic models to reveal the early population of Cyprus.

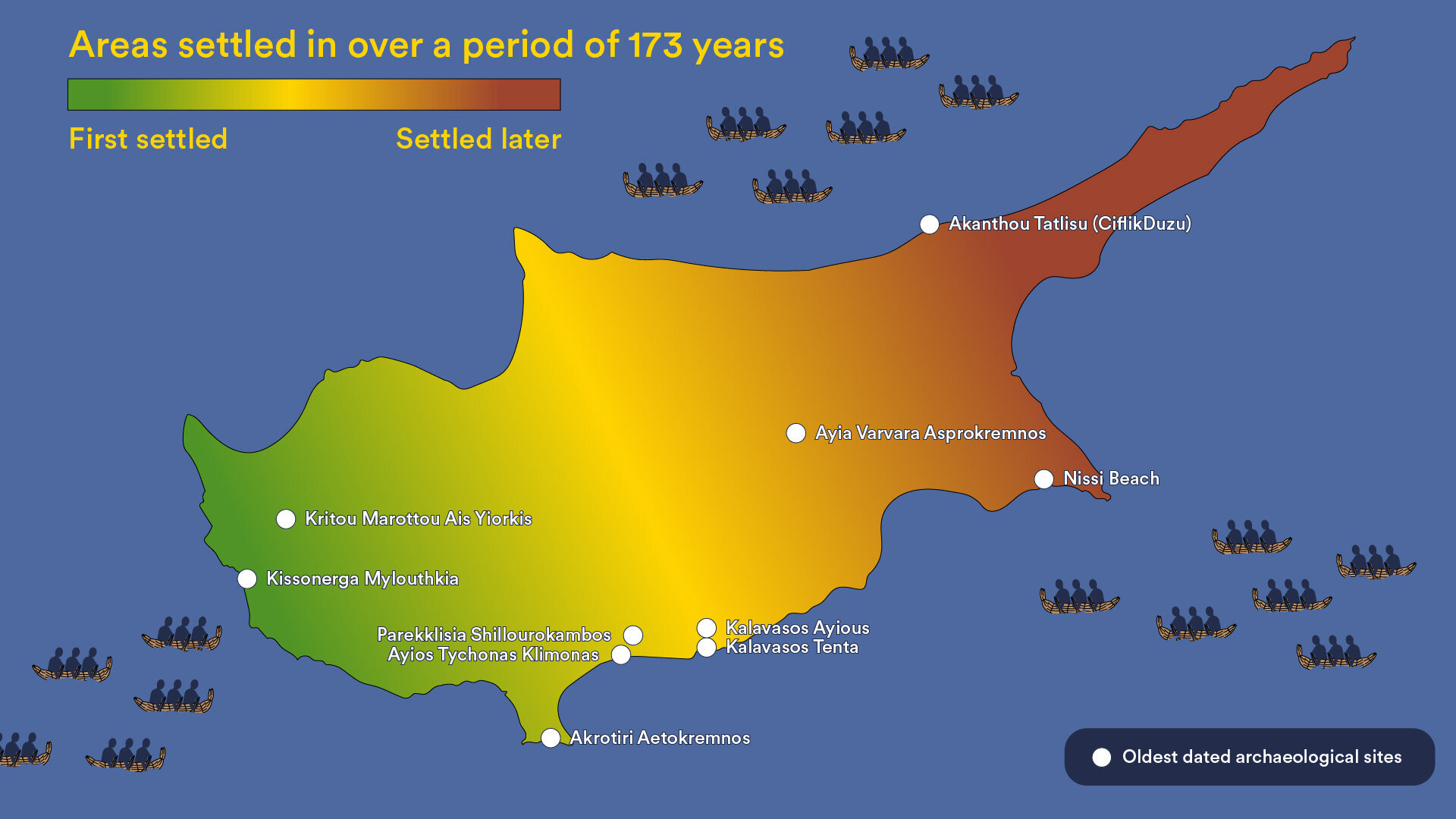

Analysis of archaeological dating from the 10 oldest sites in Cyprus suggested that the first human occupation occurred between 14,257 and 13,182 years ago, which is much earlier than previously thought.

The researchers say the island quickly settled after that. Climate models indicated that this early population coincided with increases in temperature, precipitation, and environmental productivity sufficient to sustain large populations of hunter-gatherers.

Based on demographic models, the authors suggest that large groups of hundreds to thousands of people arrived in Cyprus in two to three major migration events in less than 100 years.

“This settlement pattern involves organized planning and the use of sophisticated watercraft,” says Professor Bradshaw.

Within 300 years, or eleven generations, the population of Cyprus had expanded to an average of 4,000 to 5,000 people.

Dr. Moutsiou says the results show that Cyprus and perhaps other Mediterranean islands, rather than being inhospitable, would have been attractive destinations for Paleolithic hunter-gatherer communities.

It is argued that human spread to and settlement of Cyprus and other islands in the eastern Mediterranean is attributed to demographic pressure on the mainland, after abrupt climate change inundated coastal areas due to post-glacial sea level rise, forcing the farming population to new lands to move. out of necessity and not choice,” he says.

Dr. Reepmeyer adds that this interpretation was due to major gaps in the archaeological record of Cyprus, arising from the differential preservation of archaeological materials, conservation biases, uncertainties associated with dating and limited DNA evidence.

“Our research, based on more archaeological evidence and advanced modeling techniques, is changing that,” he says.

Professor Bradshaw says the new research findings highlight the need to re-examine the issues of early human migration in the Mediterranean and test the validity of observed early settlement dates in the light of new technologies, field methods and data.

More information:

Corey JA Bradshaw et al., Demographic models predict the arrival of the end of the Pleistocene and the rapid expansion of pre-agropastoralist people in Cyprus, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2318293121

Magazine information:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences